“Midway upon the journey of our life / I found myself in a dark wilderness, / for I had wandered from the straight and true” (Alighieri 1.1–3). What did the great poet Dante mean by this enigmatic passage? For the modern audience, footnotes, appendices, and glossaries help guide our reading. Though Dante did not tell us what he meant himself, we can thank medieval manuscript commentators for laying the foundation for the rich interpretations we study today. Dante’s Divine Comedy is an epic poem composed in the Italian vernacular in the early 14th century. In it, Dante traverses Hell and Purgatory with the help of his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, and Paradise with his muse, Beatrice. As a widely-circulated medieval classic, the analysis found in its margins can serve as a gateway to understanding the broader tradition of literary commentary. This paper explores medieval reading culture, the materiality of medieval manuscripts, the purpose of glosses, their impact, and how they take shape today.

The verses of the Divine Comedy’s first canticle, Inferno, provide insight into popular medieval reading culture. In Canto Five, Dante and Virgil meet the characters Francesca and Paolo in the second circle of Hell reserved for the lustful. When Dante requests to hear the story of their perdition, Francesca explains that she and Paolo “were reading for delight” when they succumbed to their desire for one another (Alighieri 5.128). This short passage highlights the reading culture of Dante’s time — by the 14th century, people had already begun to read for pleasure beyond religion and record-keeping. But reading was not as simple as merely understanding the words on the page, as Francesca and Paolo had done. In a letter to his patron, Cangrande della Scala, Dante shares that there were four methods of interpreting literature in Medieval traditions — literal, metaphorical, moral, and allegorical. He composed his work in line with these interpretative layers, and the glosses of medieval commentators allow us to better understand the depths of his arguments in the context of his time, especially as literature’s reach was broadening (Arduini, 2023).

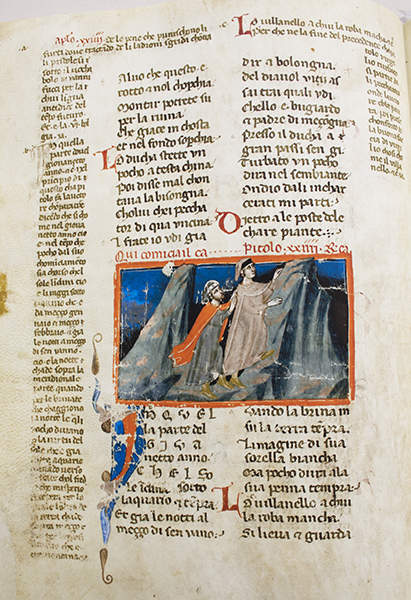

Despite the existence of intensive manuscript commentary on the Divine Comedy, there are no surviving manuscripts in Dante’s hand — scholars believe that he dictated his work to scribes. Manuscript books were individually commissioned and expensive, as parchment was made from untanned animal hides and manual copying took extensive amounts of time. The oldest surviving manuscript of the Comedy dates between 1333 and 1345 and includes glosses written by Dante’s son, Jacopo Alighieri (see Figure 1). These commentaries in the margins of the manuscript provide interpretive guidance into Dante’s poetic intricacies. Through his annotations, Jacopo shares his interpretation of his father's work with the world, contributing to the ongoing dialogue surrounding Dante's Commedia and providing valuable political, cultural, and historical context (Arduini, 2023).

Figure 1. Page from an original Divine Comedy manuscript. From “Dante's Divine Comedy and the Complutensian Polyglot Bible (1514)” by Francis T. Conserette, The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Memorial Library, 22 March 2017, https://sites.scranton.edu/library/2017/03/22/dantes-divine-comedy-and-the-complutensian-polyglot-bible-1514/.

To better understand the significance of glosses and how they shaped the literary landscape, we must travel back in time to examine the evolution of medieval literary culture and commentary on the Bible. To reach the form of books we are familiar with today, civilizations iterated from clay tablets and papyrus rolls to codices. Medieval glosses were mostly found in parchment codices, as it was the only material readily available in Europe at the time (Kilgour). Following the codex’s inception, the majority of people working with written text were members of the clergy, and around a third of early codices found before 400 A.D. were Biblical texts (Kilgour 54). The new format facilitated information retrieval and allowed them to supplement religious discourse with written sources. Reading and writing were initially a religious and scholarly undertaking in Europe due to the scarce resources they demanded. But as literacy became widespread and silent reading became popular, the domain of readership also began to expand to privileged lay people. For example, through the pecia system, stationers rented books to students to make their own copies, rendering books more available (Taylor).

Members of the clergy initially developed glosses to annotate the Bible. Glosses, which began as brief notes consisting of a few words, evolved into full commentaries over time (Cengage). As they developed, the layout of books also changed to accommodate their robustness. Scribes wrote glosses in the margins surrounding the main two-column text (Taylor). Their expansion dictated the amount of main text present on the page, often aligning with marks like our modern paragraph symbol (¶) for easy identification (Copeland). The visual hierarchy of glosses was established through font and size variations, crucial for managing the density of information on the pages. At times, they even overflowed onto the following pages, leading to the development of tie-marks to indicate “where the gloss stopped on one page and where it continued on the next.” Cristian Ispir, a medieval and Latin scholar, compares glosses and tie-marks to modern internet hypertexts and hyperlinks. They enabled readers to access a wealth of information without leaving the page and also served as handy location indicators (Ispir). By the time the most notable example, the Glossa ordinaria, or the “standard gloss”, for the Bible was developed, scribes had perfected the layout system for glosses in the margins of books (Copeland). Due to its robustness, authority, and popularity, some even say that “The Gloss, in some sense, had become the Bible” (Taylor).

Clerical habits gradually expanded to “ever broadening circles of lay people”, but their purpose remained the same — to educate (Taylor). Glosses enabled books to become knowledgeable teachers, fully explaining their content to their most faithful pupil, the reader. Professional readers existed to thoroughly understand texts and transmit their knowledge to future readers through annotations, cross-references, and catalogs. Interlinear glosses served to clarify grammar and syntax, while prose commentary helped clarify allegorical meanings, historical contexts, and allusions. There were two main types of prose glosses: those written directly on the manuscript along with the author’s original text and freestanding lemmatic commentary that used “the word or group of words from the original text that is quoted to refer back to the passage under consideration” (Copeland). Manuscript glosses resemble footnotes in today’s printed books, while freestanding lemmatic commentary more closely resembles book review and critique articles. However, they often bled into one another. Some scribes or commentators would copy freestanding commentary into the margins of their manuscripts, while others compiled margin commentary into freestanding works. Explicitly, these glosses tell us about widely accepted interpretations of literature, while implicitly, they tell a story about the culture, reception, and experience of texts. Glosses added depth to literary interpretations that would not be possible without the knowledge of the commentators and uncovered a diverse network of contemporary influences, inspirations, and connections.

Yet, the tradition of adding commentary to manuscripts sometimes leads to interpolation issues where annotations or additions are mistaken as part of the original work. For example, Servius, a well-known commentator of Virgil’s Aeneid, cites an awkward and repetitive episode about Helen of Troy as a separate text. Yet the Helen Episode appears in late-medieval manuscripts of the work, indicating some confusion in the transcription process. In another instance, Zanobi da Strada inserts a “dirty supplement” to Apuleius’ novel, Metamorphoses, involving a mature woman and a donkey (Rota). Because transcription is not standardized, people edited and “corrected” texts based on their own opinions, knowledge, and cross-examinations (or, in some cases, their idiosyncratic senses of humor). While these errors do not change the meaning of the texts, they highlight the fluidity of manuscripts, the written tradition, and the challenges for modern scholars studying them.

Remnants of manuscript commentary prevail today. Many books we read, including Dante’s Inferno, include a robust table of contents, appendices, footnotes, margins, editor’s notes, prefaces, introductions, and so on. These parts originate from medieval traditions that initially allowed the clergy to easily reference religious texts and sources. Introductions and prefaces model freestanding lemmatic commentary, while footnotes parallel the glosses in the margins of manuscripts. As media forms expand, so does the landscape of annotation. Multimedia platforms offer new avenues for interactive engagement with texts, where hyperlinks, embedded videos, and interactive graphics serve as modern equivalents of medieval glosses. Furthermore, the democratization of education has led to a proliferation of creative forms of annotation — online forums, social media platforms, and digital annotation tools enabling readers from diverse backgrounds to discuss their insights and interpretations. And, as print books have become cheap and accessible, who could forget the good old practice of writing in the margins of a favorite (non-library) book? This democratization has not only expanded access to knowledge, but has also enriched the discourse surrounding texts, fostering a collaborative and dynamic approach to literary analysis that echoes and amplifies the spirit of medieval commentary traditions.

The examination of medieval manuscript culture and the tradition of glosses reveals not only the materiality of literary works, but also the layers of interpretation that have shaped our understanding of texts like the Divine Comedy. Glosses and commentary give us a glimpse of medieval reading practices, intellectual landscape, and educational methods, highlighting the fluid nature of human ideas peeking through the static impression of written language. The authors may be dead, but their ideas live through their words. The tradition of annotated books and marginalia marks the ongoing conversation between the author, scholars, readers, and the world.

Works Cited

- Alighieri, Dante. Inferno. Edited by Anthony Esolen, translated by Anthony Esolen, Random House Publishing Group, 2002.

- Arduini, Beatrice. “Dante's Divine Comedy.” Lectures, ITAL 262, Fall 2023, University of Washington.

- Cengage. “Glosses, Biblical.” Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/glosses-biblical. Accessed 10 February 2024.

- Conserette, Francis T. “Dante's Divine Comedy and the Complutensian Polyglot Bible (1514).” The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Memorial Library, 22 March 2017, https://sites.scranton.edu/library/2017/03/22/dantes-divine-comedy-and-the-complutensian-polyglot-bible-1514/. Accessed 10 February 2024.

- Copeland, Rita. "Gloss and Commentary." Edited by Ralph Hexter and David Townsend, The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Latin Literature, Oxford Handbooks, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195394016.013.0009. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

- Ispir, Cristian. “Glossed Bibles, Hypertexts and Hyperlinks.” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, 29 January 2018, https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2018/01/glossed-bibles-hypertexts-and-hyperlinks.html. Accessed 10 February 2024.

- Janes, Joseph. “The Record of Us All.” Lecture, INFO 357, 7 February 2024, University of Washington.

- Kilgour, Frederick G. The Evolution of the Book. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Rota, Gabriele. “Classics in Slices: Scattered Thoughts on Interpolation-Criticism.” Antigone, 25 June 2022, https://antigonejournal.com/2022/06/interpolation-criticism-latin/. Accessed 10 February 2024.

- Taylor, Andrew. "Readers and Manuscripts." Edited by Ralph Hexter and David Townsend, The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Latin Literature, Oxford Handbooks, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195394016.013.0008. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

Attributions

- Photo by Krisztina Papp on Unsplash