Problem Space

A kitchen is an area that is used to prepare food (“Kitchen Definition”). Though it can exist in other contexts, such as in restaurants, this exploration focuses on it in the context of living spaces shared between more than one individual. German architect Gottfried Semper views architecture through an anthropological perspective and defines it as consisting of four elements — the hearth, the roof, the platform, and the walls. The hearth is a space for fire, and, by extension, cooking, gathering, and eating. It is “the first sign of human settlement” around which the remaining elements of architecture were born (101–102). In other words, the hearth, which has evolved into the modern kitchen, is the center of domestic life and has social origins. Cooking, the process of using heat to transform the physical properties of food, falls within the broader activity of food preparation, the process of rendering food edible. Though eating is a basic biological need, the act of preparing food can serve as a form of social bonding. Aristotle defined it as a “menial art”, indicating that at one point in history, it was viewed as a chore requiring little skill. This is also a view that many carry today. The act of preparing food is associated with “the household and daily routine”, so it is typically viewed as insignificant, and its social value is not prioritized. Despite being overlooked, the act of food preparation is crucial in revealing social relations both in society and within households (Graff 1–6, Paay 276–278).

Stakeholder Engagement

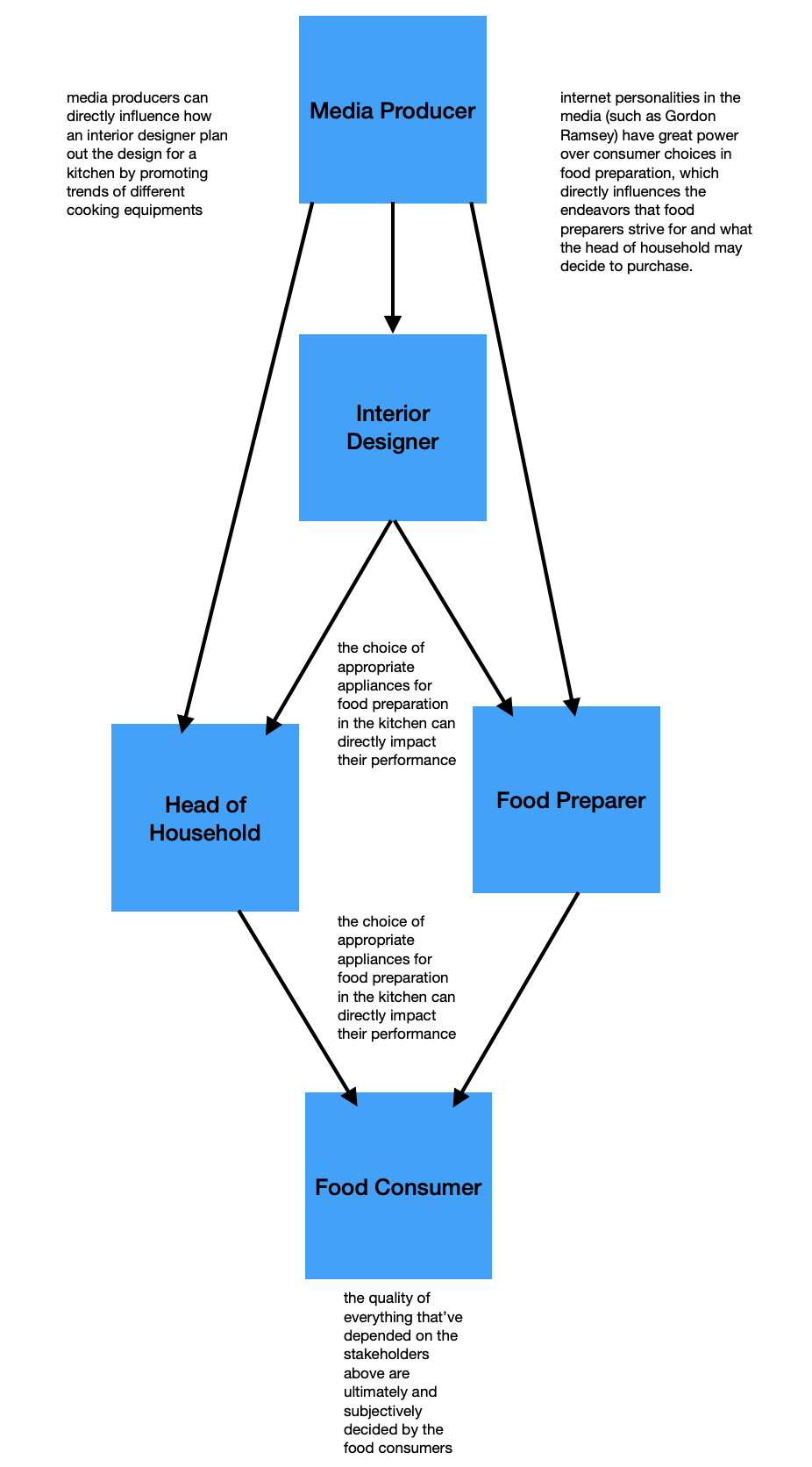

Key Stakeholders

Preparing food in shared spaces requires high levels of communication between core stakeholders. As all members of a domestic household — whether family members, roommates, guests, or other relations — must eat, they all are invested in and affected by the preparation of food in the kitchen. They must coordinate how food is stored, prepared, and consumed, as well as decide what food supplies to replenish, when to do so, and who is in charge of doing so. Tertiary stakeholders such as food media producers and interior designers are not as invested or affected but have a strong influence over how food is produced and how people interact in and with the kitchen space. Some key stakeholder groups include media producers, interior designers, head of household, food preparers, and food consumers, as shown in below.

Contexual Interviews

For our contextual inquiries, we focused on the specific stakeholder group of “food preparers”, as we felt that they had the most interactions with the physical space itself. We interviewed five college students living with roommates, as these were the stakeholders that we had ready access to. In some interviews, “food consumers” (i.e. roommates, friends) were present, and we included them in the process, too, as they help illustrate the candid, daily use of a shared kitchen space. By observing these areas, we were able to better understand how the participants collaborated, communicated, and prepared food with those who share their space.

Intervention

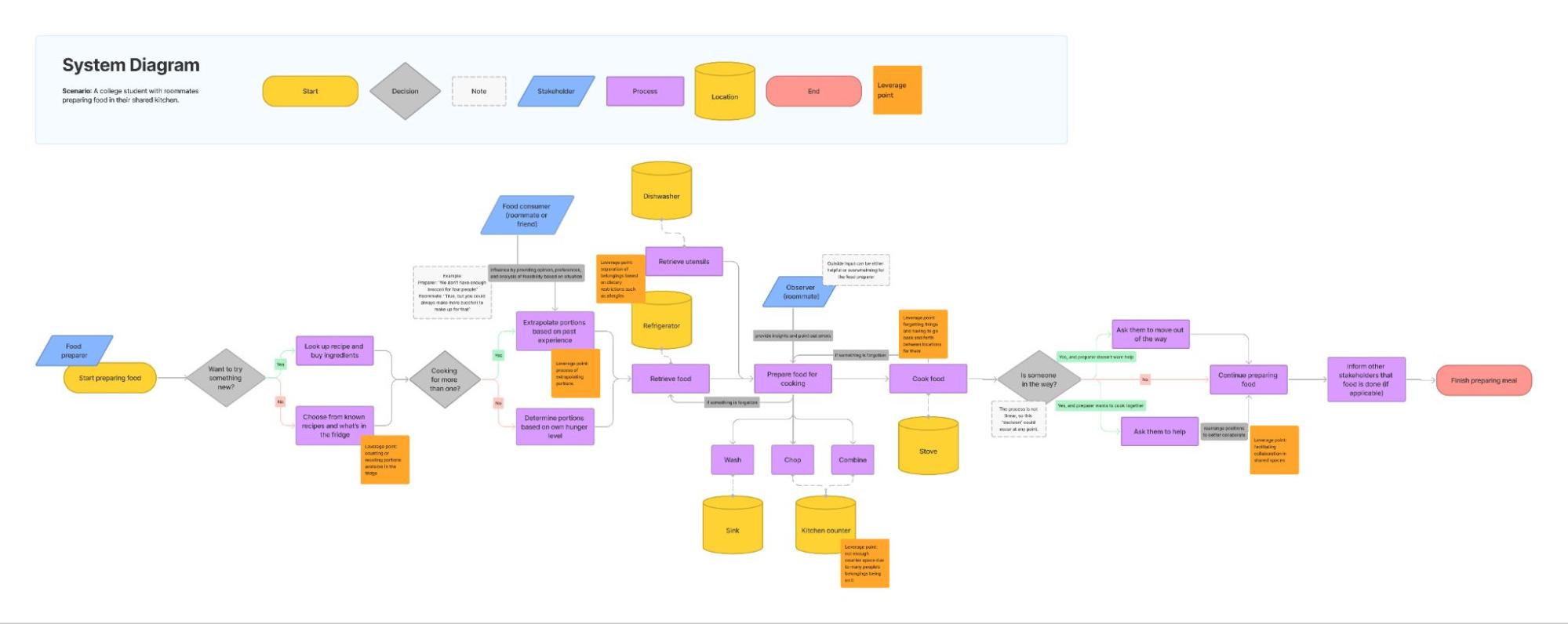

View full system diagram on Figma

View full system diagram on Figma

Though the process of preparing food in shared spaces is a complex undertaking, we decided to simplify it at a macro level to identify and represent the potential leverage points more clearly.

For some, preparing food can be a social activity (Graff 1–6). As people interact in the kitchen by changing their physical position in the space, there is potential for streamlining the process through technological interventions to better "connect, converse, coordinate, cooperate and cook" (Paay). It would be preferred if individuals who are cooking could move through the space fluidly and document what they learned from the collaborative experience. The design space that we chose is the management of the shared kitchen space. With the goal of improving communication between housemates and overall experience in mind, our design concepts aim to combat issues such as scheduling conflicts and distribution of space.

We considered the below points of intervention based on the contextual inquiry conducted with our participants in their shared kitchen space. We noted that many of her struggles involved portion control, efficient use of space, and sharing food items. As we observed, we noticed that many of these pain points were solved with the help of her housemates.

Leverage Points

Potential points of intervention that we identified include:

- Counting or recalling portions available in the fridge

Why: Our contextual inquiry participant spent a significant amount of time standing in front of the refrigerator assessing what ingredients she had and how much of them were present.

- The process of extrapolating from past experience to determine portions

Why: Our participants adjusted portion sizes on the fly to feed the people within their domestic space on that given day. However, in the end, there was not enough food to satisfy everybody.

- The separation of belongings and food items based on dietary restrictions such as allergies

Why: Our participant mentioned a roommate with severe allergies who separated her kitchen utensils from the rest of the household. She is very meticulous about this separation, as any mistake could result in severe consequences. Additionally, another stakeholder stated that her roommates separated their belongings as well due to differences in dietary preferences — she eats meat, while her roommates are vegan.

- Not enough counter space due to the presence of too many people’s belongings

Why: Our participant kept dropping food and moving objects around because of the limited counter space available in the shared kitchen space.

- Forgetting things and having to go back and forth between locations within the space to retrieve them

Why: Our participant’s cooking time was significantly lengthened by inefficiency in this department. She kept going back and forth between cutting, retrieving, and washing food items because she did not plan everything out beforehand.

- Facilitating collaboration in shared kitchen spaces

Why: We noticed this was something that occurred regularly within shared kitchen spaces, even if collaborators were not actively participating in the cooking process. Therefore, it may be beneficial to consider how this process could be made more enjoyable and rewarding for the stakeholders involved.

To determine these leverage points, we referred to our previous contextual inquiry and conducted informal interviews with additional stakeholders to gain more perspectives. With our intervention, we hope to improve the collaborative aspect of the shared kitchen environment through experimentation of communication means. Rather than implement physical products that would interact with and obstruct the kitchen space itself, we opted for a subservient approach through the use of technology. By observing the ways in which we can improve communication within the shared kitchen space, we also wanted to provide a way to make progress visual and commemorative (Factor, 2020). The main goals we have for our intervention are improving communication between housemates, improving the management of inventory, and promoting better health habits.

Design Concepts

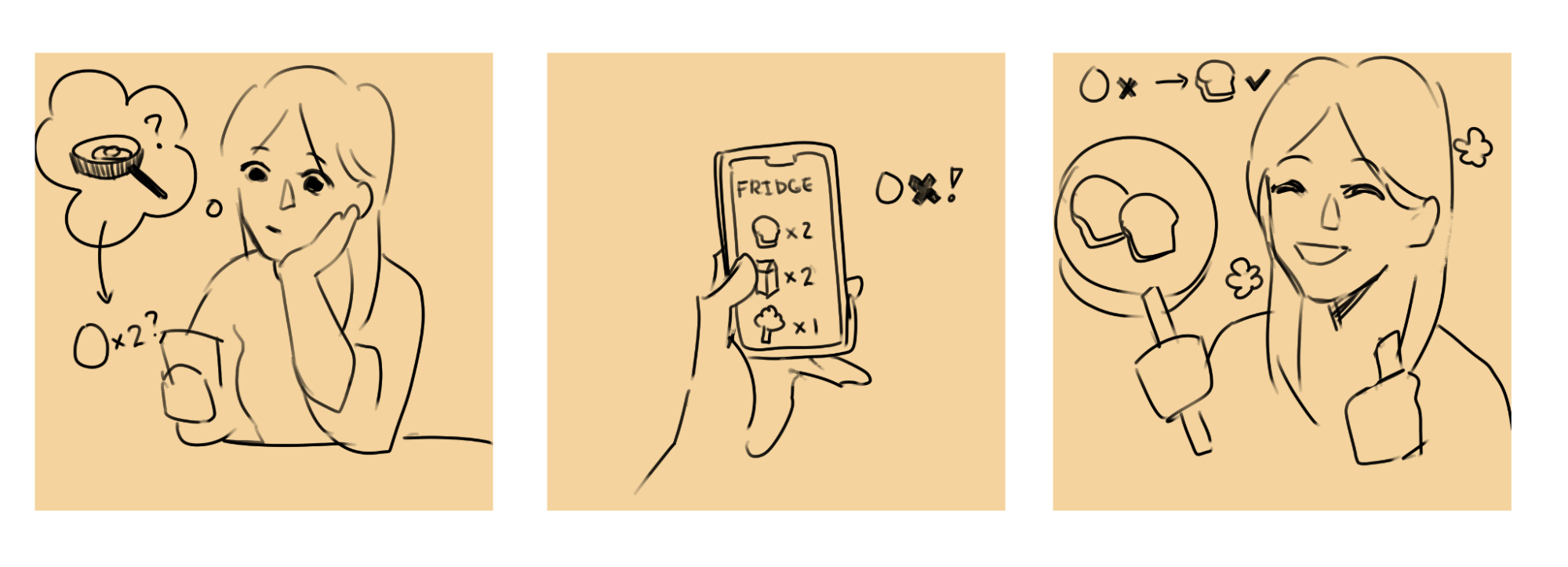

Housemate Fridge Inventory

This intervention pinpoints “Counting or recalling portions available in the fridge” as a leverage point. It will allow housemates — or people who share kitchen spaces in general — to view the items available in their fridges at a glance. This would save them the hassle of counting and assessing every time they need to cook, and can also help outside of the kitchen space, such as when grocery shopping. This intervention changes the system by making the process of retrieving food from the fridge, communicating between stakeholders, and managing food supplies smoother.

The storyboard above depicts a stakeholder who wants to make something from a recipe but is not sure if they have the ingredients needed (eggs) in the fridge. Rather than rummaging through the fridge to see if they do have eggs, they instead check the inventory application. They discover that they do not have eggs, but do have bread. Therefore, they make toast instead of eggs.

Though the leverage point may be considered a small inconvenience, we chose it because we noticed that it would, in our contextual inquiry participant’s case, save a lot of time and effort. The storyboard simplifies the situation, but there could be cases where the desired ingredient requires some rummaging to get to. We also personally find checking the fridge a point of high friction that sometimes causes me to not cook at all when we are feeling tired from other things in life. we chose the form of a mobile app because it is portable and data is easily shareable, which makes it easy for housemates to update information in real-time and check what food they have at home while on the go.

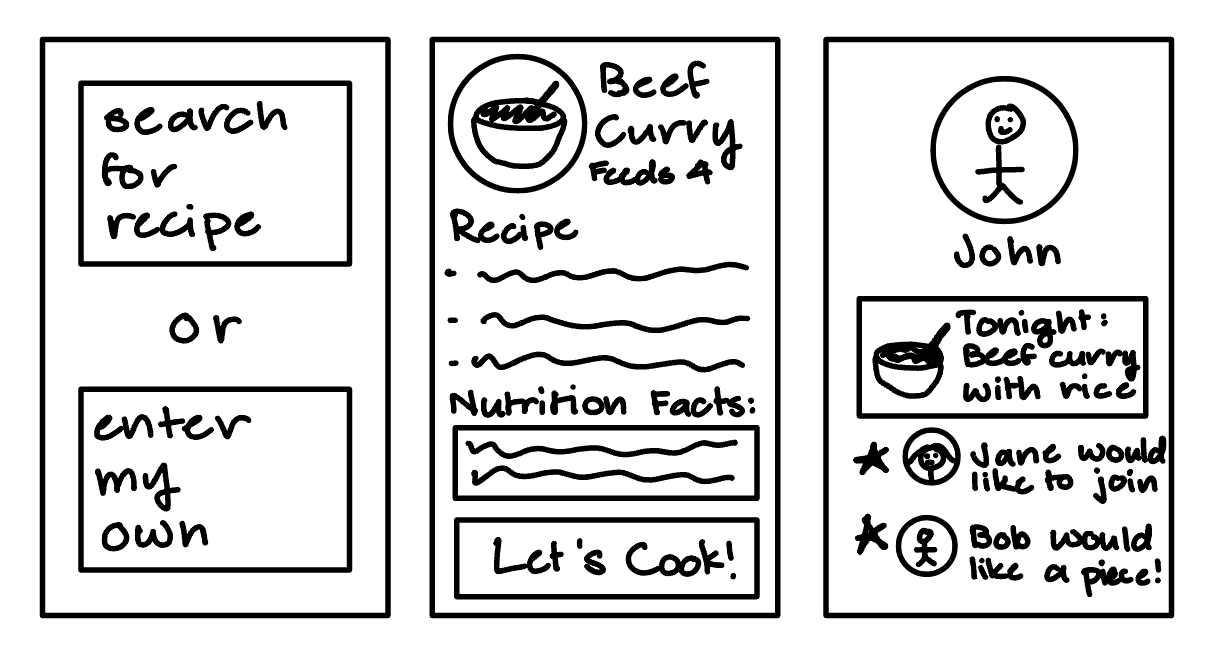

Portion Sizing

This intervention focuses on the leverage point of extrapolating portions. Determining portion size is dependent on the cooking experience of the individual and their recollection of past cooking experiences. The main problem is that determining portion sizes when cooking for multiple individuals can pose a challenge when trying a new recipe or if the individual is new to the cooking experience. This intervention aims to determine portion sizing for multiple individuals, as well as provide a means of communication between housemates.

The application sample demonstrates the application providing an alternative means of communication between housemates while also providing recommended portion sizes. The application first takes user input for the specific dish, which can be inputted by the user or imported via URL. If the recipe is user-inputted, they will need to provide the ingredients required and the number of portions the dish produces (for the first time only). The application will then save to a user’s profile and create a digital cookbook. After the dish is selected, the user’s profile will then share the dish being prepared with the other housemates. The housemates are then able to vote if they would like to consume the dish and the application will adjust the ingredient portions accordingly.

One of the biggest challenges for us when cooking is determining portion sizes and without a recommended portion size, we often find ourselves overeating. In addition to portion sizes, the additional cookbook feature assists users when determining what to cook. We often go to the grocery store with no set plan for a meal and it’s not until we see certain ingredients that inspire me to make a dish. By having this reference that is easily accessible, we anticipate that it would assist in the amount of time spent at the grocery store and eliminate the indecisiveness that’s associated with choosing a dish.

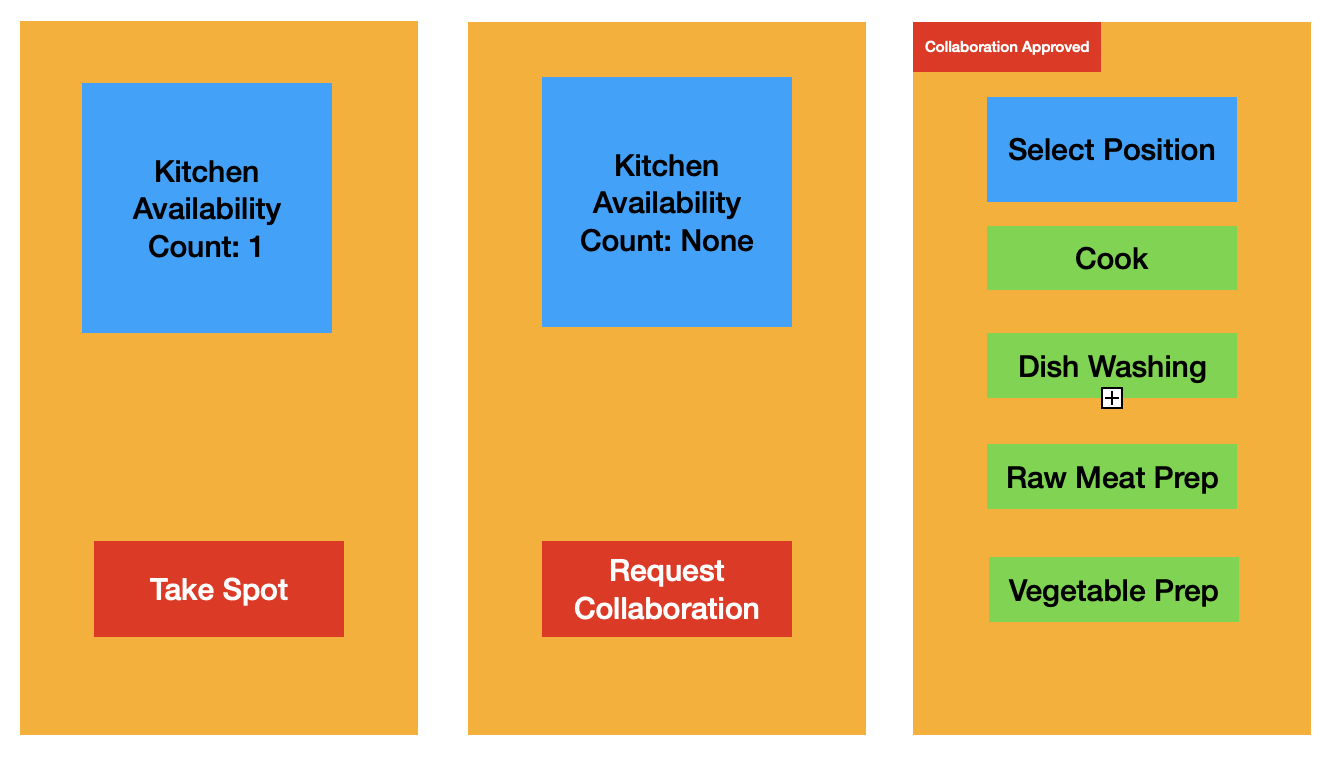

Cooking Collaboration

The above illustration gives a rough idea of what the application can do. Everyone living in a household or who shares a kitchen will have this app on their phone and take the spot if they need to cook. If someone else is cooking just for themselves, they have the option to let one join them or decline them. If someone else is cooking for this entire group, one can request to join that working person and pick a position to help. There are many different ways for a group of people to prepare food together and save time as a whole: in particular, one can do all the cleaning work for the dishes, one can cut out all the vegetables and fruits, one can prepare the raw meat, and the last one being the book. With this application, we think it will be a lot easier for everyone to play a role during the making of their food and drastically reduce their workload, time wasted, and energy & water used.

Final Choice

We decided to go with the first design concept that focuses on the intervention of recalling portions within the fridge. We ultimately landed on this choice due to this intervention point being one of the foundational decisions within our system diagram. Through our contextual inquiry, we observed that our participants along with their household members, also faced a similar struggle when recalling ingredients and determining what to cook. Although similar applications exist such as Cookpad and SuperCook, these often don’t account for portion sizing and are limited to in-app recipes.

Proof of Concept Prototype

Prototyping Process

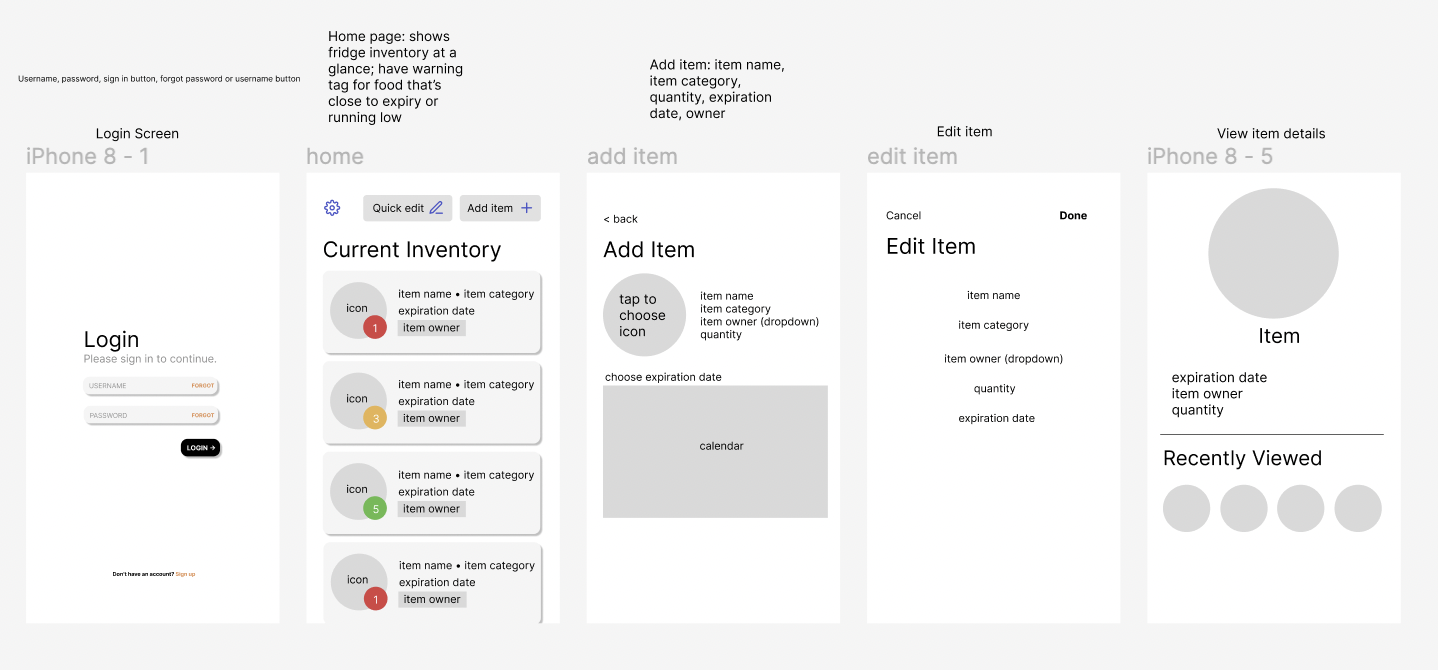

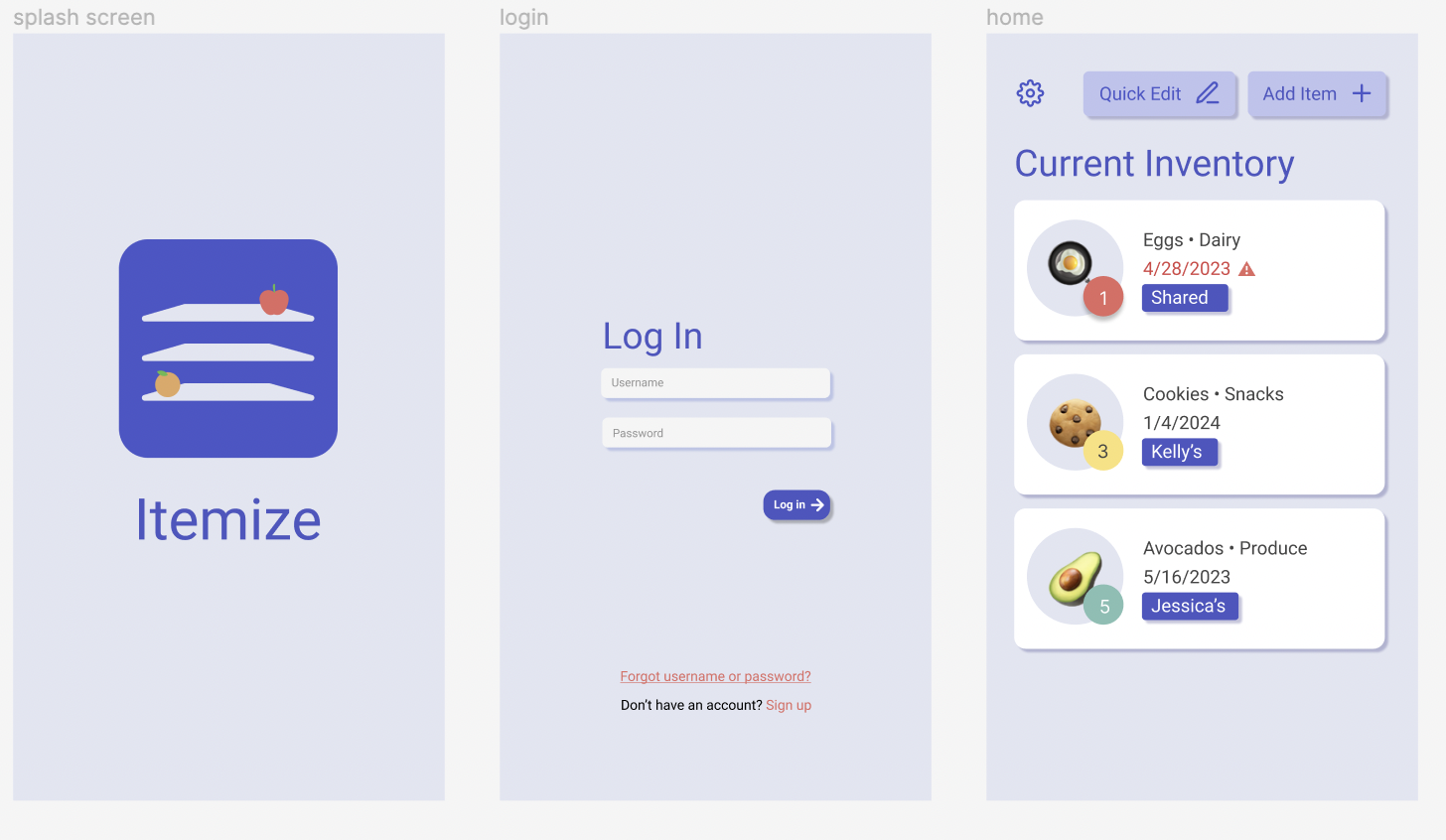

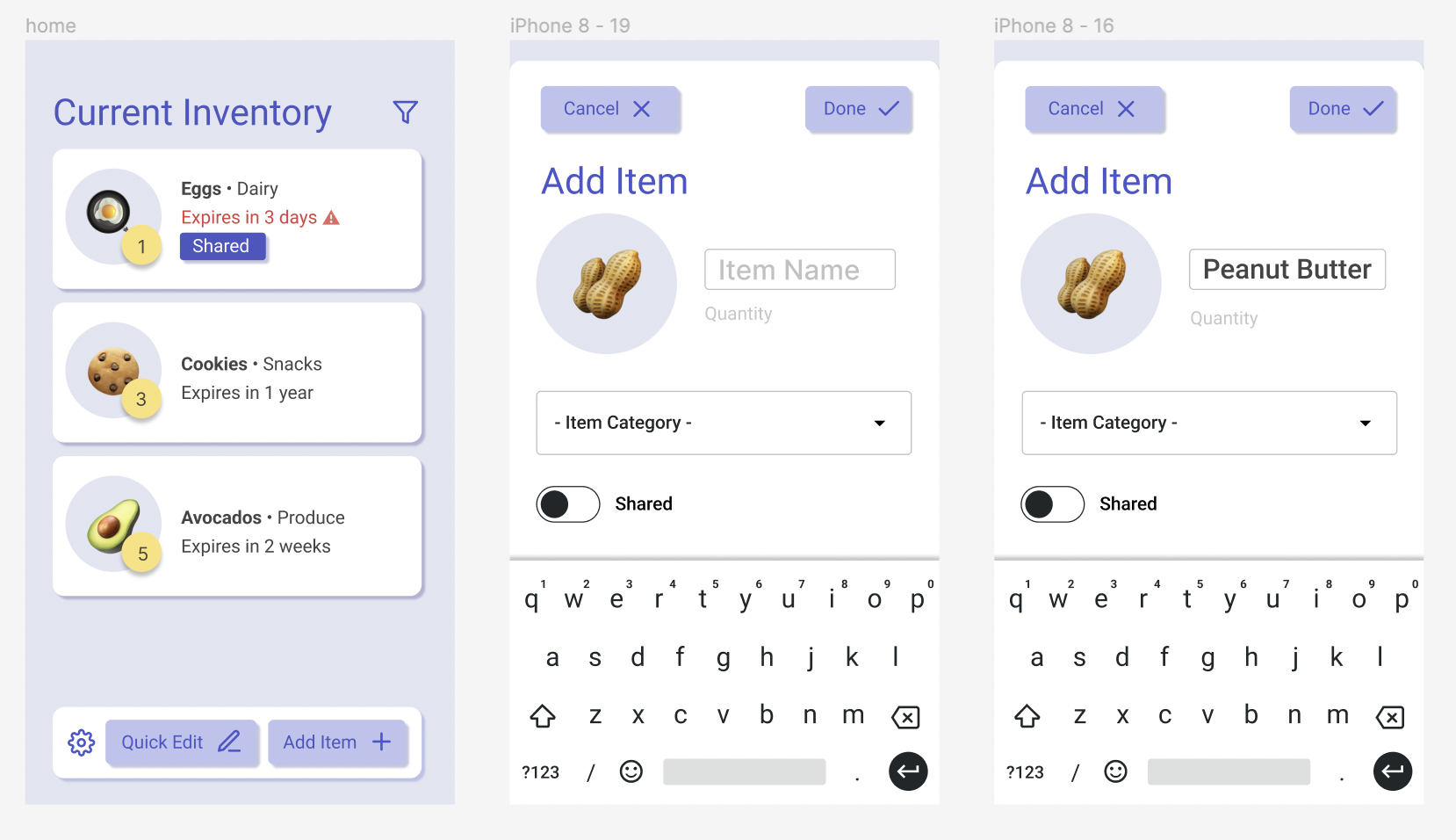

In our low fidelity wireframes, we decided to make five screens: login, the home page, add item, edit item, and view item details. Like our logo, we decided to create a minimalistic user interface and rounded edges to match the aesthetic of our logo. Through our first round of wireframes, we found that the ‘view item details’ page seemed a bit redundant and quite similar to the add pages and edit item pages.

The name ‘Itemize’ came up in one of our wireframing discussions. It accurately describes the cataloging of fridge items and organizes them in a way that maximizes space within a shared environment. Our high-fidelity prototype features a colored version of our low-fidelity wireframes in a way that is user-friendly. It is a semi-functional interactive prototype that details the scenarios of various functions. The “Add Item” function depicts the process of adding a new item to the user’s inventory. The user can choose to name the item, quantity, category, owner, and expiration date. We found this function to be a bit lengthy and so we incorporated a “Quick Edit” function to allow the user to change the quantity of a given item without having to go through the add item screen. The last function we implemented was the ability to change the owner of a given item. Again, we wanted the process to be efficient so that the user could perform this function from the “Current Inventory” page. To execute this function, the user can simply select the owner under the given item, which will display a dropdown list with all the previous owners, a shared option, and the option to add a new owner. We ultimately decided to focus on the three most essential functions that would make our application efficient while maintaining simplicity.

Branding

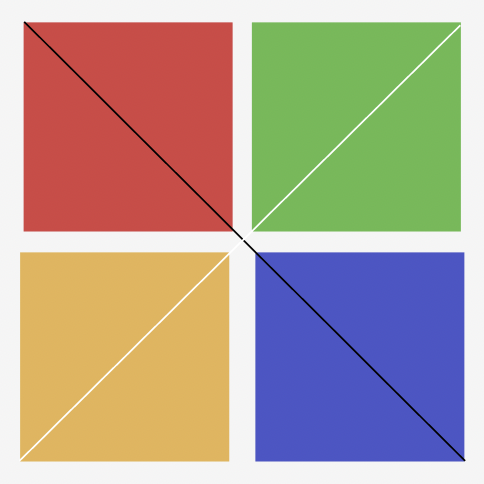

When making a food-related application, we noticed that a good majority of food application logos contained vibrant primary colors. With this in mind, we came up with a preliminary color palette that featured the three primary colors as well as green. While experimenting with black and white as potential text colors, we found that both had approximately the same readability with this specific color palette.

We wanted to incorporate some elements of the fridge into our logo since it’s an app that primarily focuses on fridge inventory and storage. In the first draft, our logo (left) took the literal interpretation of a fridge and made the appliance into a monochrome minimalistic design. At first, we liked the idea of using green as our primary color since it would make our app distinguishable from others. However, after careful consideration, we ultimately decided against the green color due to its similarity to other mobile non-food related applications such as messages and phone logos. In the second iteration of our logo (center), we decided to focus more on the storage and inventory concept. It features a three-tiered shelf, similar to that of a fridge and an apple to convey that this was a food-related application.

Following modern design trends, we decided to make some small modifications to the second iteration of our logo (right). We rounded the corners of the shelves and edges of the application to give a more appealing look and a comforting feel. In addition to the shelves, we added an orange to give the logo a symmetrical balance. Lastly, we slightly altered the color of the shelves from the wireframing gray color to an off-white.

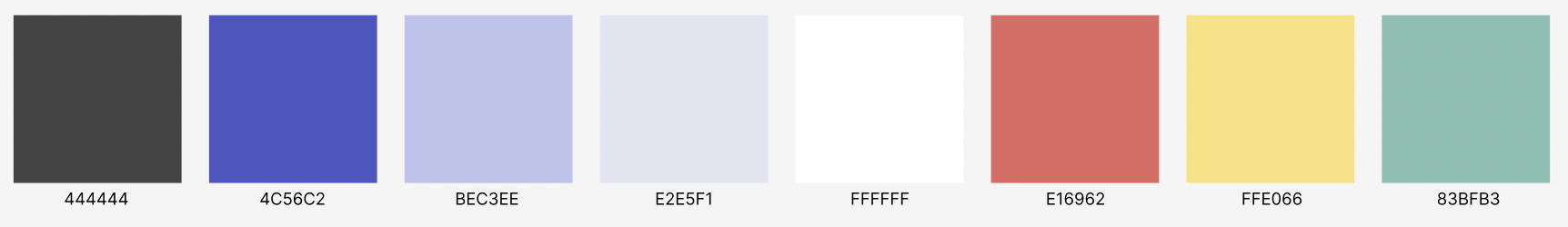

After determining the blue background color of our logo, we decided to build a color palette based on the colors that would complement each other. We used the website coolors.co to begin generating randomized color palettes and color palettes with the addition of our blue primary color. Taking inspiration from the two palettes generated, we then altered the colors until we landed on our final color palette. It features two text colors (gray, white), a monochrome scale of the original blue, and a stoplight set of colors as accents (red, yellow, green).

Evaluation

We elected to evaluate our intervention using usability testing and surveys. These methods are appropriate for thoroughly testing the look and feel, as well as the potential implementation, of a mobile application. Usability testing will allow us to delve deeper into our app’s navigation and information architecture issues, while surveys will allow us to prioritize features and better align our goals with stakeholder needs.

Since we are focusing on the dynamics of the shared kitchen space, we recruited college students to participate in our evaluation, as many either live at home with their families or live in shared spaces with roommates. We first sent out surveys through connections and social media for impressions on our intervention from a broader perspective. While we do understand that this is a form of convenience sampling, the act of sharing a kitchen space with others is one that everyone has experienced at some point in their lifetime. The survey introduces the design and proof of concept prototype to the respondent, then gauges how useful they deem the features to be. While we were gathering survey responses, we conducted usability tests both online and in person to maximize accessibility for participants.

Survey

We received 35 responses to our survey. None of the respondents usually keep a list of items in their kitchen. 74.1% of respondents would use the app, 11.4% would not, and 14.5% would “maybe” or conditionally use it.

The questions we asked were:

- Do you usually keep a list of what food items you have in your kitchen? (Yes / No / Other)

- Would you incorporate this application into your daily life? (Yes / No / Other)

- If yes, how would you see yourself interacting with it? If no, why not? (Open)

- On a scale of one to seven, how likely would you be to reference this application while cooking? (1–7)

- On a scale from one to seven, how likely would you be to reference this application while grocery shopping? (1–7)

- On a scale of one to seven, how useful would it be to be able to see the quantity of each item in your fridge through the app? (1–7)

- On a scale of one to seven, how useful would it be to be able to see which items are available in your fridge through the app? (1–7)

- On a scale of one to seven, how useful would it be to be able to see who owns each item in your fridge through the app? (1–7)

Those who responded “No” or “Maybe” shared the sentiment that they would be unable to keep up with using the app due to the energy and effort required to manually input data — one respondent states that “methods usually don't last long just because they're not convenient enough and take extra mental effort to remember doing”. However, another says “If there’s a device that detects what foods are in the fridge that connects to the app then I’ll use it,” which is helpful in pointing us in a direction for future iterations.

One respondent brings up the point that if they “needed to know what was in the fridge, [they] could just open it”. One respondent answered enthusiastically, stating that they “would definitely use this app to its fullest extent”. Another respondent expresses the opinion that “it matters less who owns what items, but more [that] it’s easy to check with what shared items are low so they can be replenished“, which is useful for pivoting the focus of our intervention.

Most respondents indicated that they would be extremely likely to reference the application while grocery shopping and less likely to while cooking. The feature that is perceived to be most useful is being able to view items and their quantities in the fridge, while opinions on the feature to see who owns each item were mixed.

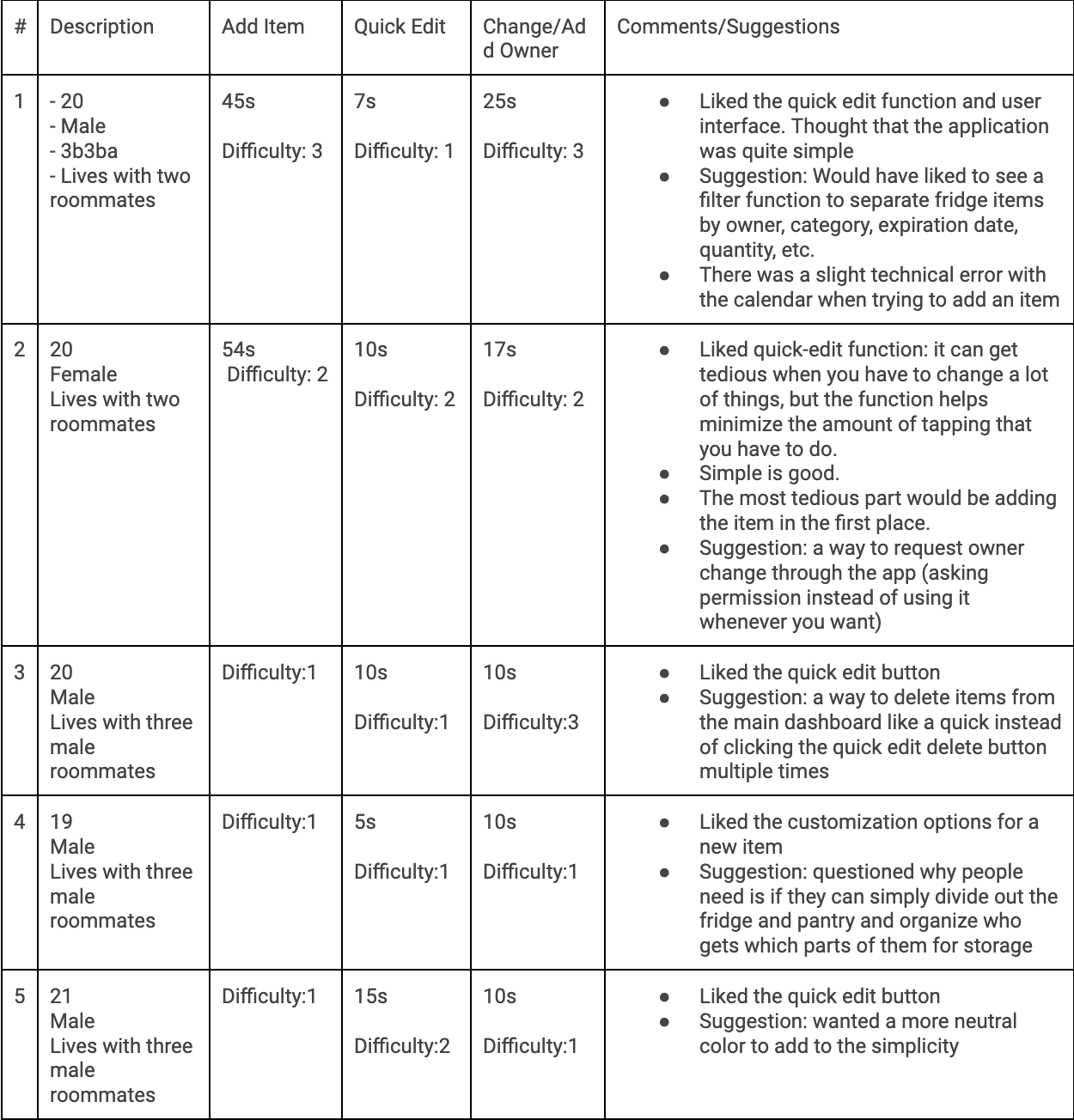

Usability Testing

We collected the time taken to complete each task, measured in seconds, and the accuracy with which each task is completed, measured in the number of errors. We also recorded the screen during interviews to document how participants interacted with the application.

Since the sample size is small due to the project's scope, we cannot expect these figures to be statistically significant enough to conduct a formal, quantitative analysis, but they will be useful in informing us of our intervention’s success.

Iterations

After receiving feedback from the INFO 360 instructor team, we revised our prototype to make the navigation more accessible for thumb reach, changed the colors of the quantity icons to be less chaotic, and made the expiration dates more understandable at a glance.

Since the feature with the highest average difficulty level was the “change owner” feature, we realized that it was a bit overcomplicated. Usability test participant 2’s response that it would be nice to request owner changes through the app indicates to us that our solution made simple communication more complicated than it should be. We used the survey response that said, “it matters less who owns what items, but more [that] it’s easy to check with what shared items are low so they can be replenished“ as a reference point for simplifying the process. This also allowed us to simplify the process of adding items, which participants said would be tedious if they had to do it for every item they purchased.

Above is the final iteration for our application.

Requirements and Specifications

Our application requires the stakeholder to have access to a smartphone that supports the software. As older operating systems often don’t support modern frameworks, we estimate that the user’s software must be less than five years old for the application to perform optimally.

In terms of technology, our intervention has minimal requirements — all the functionality can be achieved with a simple backend cloud service, such as Firebase or AWS, that has real-time database features.

Limitations

Though respondents to our survey and participants in our usability testing found the intervention useful, there is further room for improvement in our design space. We only prototyped a small portion of our intervention, which, like users mentioned in section 5.2, could be tedious to enter data into manually. Thus, further explorations could include automatic tracking and scanning as the user loads items into their fridge and cabinets. However, with the current technology available on the market, integrating such features would marginalize many of our stakeholder groups, who cannot afford fancy smart fridges and cameras to scan and track these items. We hope that, as technology advances, these small conveniences will become more accessible to populations who need to share kitchen spaces with peers.

BONUS: Speculative Design for 2123 A.D.

Scenario One

Food goes into a gelatin-like substance with microscopic probes that detect the safety of food through chemical changes. This yogurt is still good to go despite being three days past its expiration date! But, unfortunately, the pasta that you accidentally left on the counter overnight and chucked in the fridge hoping to salvage it is beyond saving. Better throw it out soon, it’s not safe to eat.

Scenario Two

Miranda opens the fridge in the middle of the night and finds that the midnight snack she was looking for has gone bad while she was sleeping! Oh well, better to go back to sleep hungry than wake up with a horrible stomach bug. She could have checked the Itemize app to see which foods were in the fridge and safe to eat, since the probes and fridge are connected to the database which refreshes live through the mobile application, but frankly, the thought didn’t cross her sleep-hazed mind. Good thing the gelatin fridge also has visual cues to indicate whether food has gone bad, otherwise, she would have just grabbed it and eaten it without a second thought.

References & Attributions

Project created with Eric Xue and Logan Hosoda for the University of Washington course INFO 360: Design Methods.

- Clifford, Dawn, et al. “Good Grubbin': Impact of a TV Cooking Show for College Students Living Off Campus.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, vol. 41, no. 3, 2009, pp. 194–200, https://www.jneb.org/article/S1499-4046(08)00010-9/fulltext. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

- Graff, Sarah R., and Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría, editors. The Menial Art of Cooking: Archaeological Studies of Cooking and Food Preparation. University Press of Colorado, 2012.

- “Kitchen Definition: 361 Samples.” Law Insider, https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/kitchen. Accessed 8 April 2023.

- Méjean, C., Si Hassen, W., Gojard, S., Ducrot, P., Lampuré, A., Brug, H., Lien, N., Nicolaou, M., Holdsworth, M., Terragni, L., Hercberg, S., & Castetbon, K. (2017). Social disparities in food preparation behaviours: A DEDIPAC study. Nutrition Journal, 16, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-017-0281-2

- Paay, Jeni, et al. “Connecting in the Kitchen: An Empirical Study of Physical Interactions while Cooking Together at Home.” CSCW '15: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 2015, pp. 276–287, https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675194. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

- Santrach, M. (2021, April 1). Why the Kitchen Sells the Home. Studio M Kitchen & Bath. https://studiom-kb.com/why-the-kitchen-sells-the-home/

- Shustack, C. (2023, March 1). New Report Shows Social Media Is Vastly Improving People’s Cooking Skills. The Daily Meal. https://www.thedailymeal.com/1214286/new-report-shows-social-media-is-vastly-improving-peoples-cooking-skills/

- Semper, Gottfried. The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings. Translated by Wolfgang Herrmann and Harry Francis Mallgrave, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- USDA ERS - Food Away from Home. (n.d.). Retrieved April 9, 2023, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-choices-health/food-consumption-demand/food-away-from-home.aspx

- Willen, Rachel. “When Chefs Gather: How Pros Influence Home Cooks.” ABC News, 2012, https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/lifestyle/2012/10/when-chefs-gather-how-pros-influence-home-cooks. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

- 2021 U.S. food-away-from-home spending 10 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels. (n.d.). Retrieved April 9, 2023, from http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=58364